I Want Space Without Pictureness

Catalog Essay from: Michelle Oosterbaan Installation at The Morris Gallery

December 13, 2003 – February 1, 2004

Curated by: Alex Baker, curator at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art and Museum

By: Richard Torchia, Director, Arcadia University Art Gallery

Painting is an art on the verge of exhaustion, one in which the range of acceptable solutions to a basic problem—how to organize the surface of a picture – is severely restricted. The use of shaped rather than rectangular supports can, from the literalist point of view, merely prolong the agony. The obvious response is to give up working in a single plane in favor of three dimensions.

-Michael Fried

“Art and Objecthood,” 1967

The attacks on painting in the sixties failed to specify that is wasn’t painting but the easel picture that was in trouble…I’ve always been surprised that Color Field—-or late modernist painting in general—didn’t try to get onto the wall, didn’t attempt a rapprochement between the mural and easel and picture.

-Brian O’Doherty

“Inside the White Cube,” 1967

I want space without pictureness.

Michelle Oosterbaan

Michelle Oosterbaan has advanced a hybrid practice based on the exacting use of applied color to articulate her attuned responses to interior spaces. Her projects of the past four years result from the painstaking use of adhesive tape and rectilinear fields of solid paint to manipulate our perception of—and passage through –a given room. A fluid reciprocity between the eye and the body are critical to works in which shifting views and possible meanings are contingent on the relative position of an active viewer. “It has to be physical,” she has stated, “otherwise it won’t be optical.”

Oosterbaan addresses each room she treats as a found object, a blank canvas, and an elastic territory to be mapped and traveled. She usually begins by identifying distinguishing features of the given site she wants to amplify or camouflage. In Storehouse Thaw (illustrated here) she dissolved the impact of a broad, insistent floor molding by painting a horizontal band of beige (the same width as the molding) onto the wall directly above it. Blocks of color resting on top of this bar (riffing on the adjacent windows) coalesce into a fictive “canvas.” A dark blue rectangle on the lower right of this composition reaches around the corner where it appears to slide beneath a plane of horizontal stripes that seem to drop down the wall, almost audibly, like a shade. Such maneuvers are easier to sense than to say. Although describing them may reveal Oosterbaan’s logic and motives, their full effects remain resistant to language.

Storehouse Thaw, 2003, Latex on wall. 14 x 13 x 20 feet. Partial installation view Main Line Art Center, Haverford, Pa., On the Walls

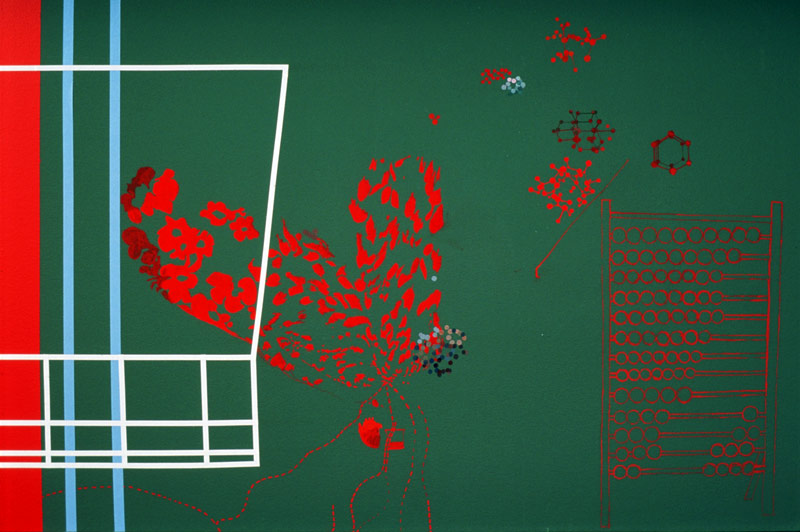

Among Oosterbaan’s goals is establishing equilibrium between the existing conditions of the given space and a fantasy projected onto it. The illusions she employs, which are always realized with practical means “derived from painting,” as she explains, are frank and effective in their seamless merger of the real and the virtual. The perceptual conundrums achieved—such as the appearance of a shadowed floor vent (But You are Here Now, illustrated here), or the recessed space she cuts out of the corner of the orange wall to match its equivalent beneath the adjacent yellow overhang in Room: Site #3 (also illustrated)—–can be confounding.

But You are Here Now (detail), 2001. Latex and adhesive tape on wall and floor. Variable Dimensions. Sharadin Art Gallery, Kutztown University, Pa., Future Imperfect.

Oosterbaan animates her work with a desire to fuse the diagrammatic to the actual. Her use of adhesive tape is expressive in this regard. Whether affixed to her folded blankets from the late 1990s or drawn across a painted wall (as in the red chart that seems to float on an invisible plane before the aforementioned recess in Room: Site #3), these lengths of tape and their precise, readymade edges read interchangeably as immaterial line and tangible substance.

Room: Site #3, 2000. Latex, adhesive tape, gouache on wall. Variable dimensions. Installation view. Project Room, Philadelphia.

A student of color and the theories that codify its behavior, Oosterbaan has cultivated a hypersensitivity to the way the eye moves across the boundaries between one hue and another, gliding over the margin between two related hues of similar value (pink and orange, for example) or faltering when confronted by sharp contrasts in temperature (orange vs. blue). The wraparound continuity that has characterized her environments helps to guide the gaze that pulls the body with it. Oosterbaan has also acutely attentive to shifts in value (the relative darkness or lightness of a color), whether caused by changing levels of illumination or the particular angles and textures of the walls absorbing and reflecting it. Compounding the capacity of paint to confuse the light and surface with the continual deception of color, Oosterbaan creates works of remarkable nuance, mystery and immediacy.

In addition to accessing involuntary, emotional responses, Oosterbaan’s color is also an instrument for measuring distance and making space happen. Thus, regardless of her intention to get as much done beforehand in the studio, Oosterbaan’s need to be on location to make decisions in harmony with the actual lighting and proximities of the given space takes precedent. The fact that she frequently mixes her own colors from surplus paint discounted from commercial sources contributes to the contingencies that define each project. In light of this, it is interesting to consider an apocryphal anecdote about Mondrian who, apparently, upon encountering one of his canvases in a gallery, was so disturbed by how a particular shade of red differed so radically from the color he recalled in the studio that he returned to the gallery the next day to repaint it.

Mondrian is an apt reference for Oosterbaan, with whom she shares not only her Dutch heritage but a penchant for clean edges and tape. His Salon for Madame B. (1926), a design proposed for a drawing room in Dresden, is a worthy precedent. The walls, ceiling, and floor of this interior are covered in squares and rectangles painted black, white, gray, red, yellow, and blue. The manner in which this décor places the spectator inside an abstract picture is echoed by El Lissitzky’s Exhibition Room (also 1926), a gallery lined with vertical strips of wood painted black on one side and white on the other thus causing the walls to change color in accordance with the viewer’s stride. Oosterbaan’s idiosyncratic colors and improvisational compositions make the utopian ideals and restricted palette of these modernist precedents seem hermetic by comparison. Inspired by a spectrum of sources, ranging from fashion design and eastern temples to snapshots documenting construction tarps and tree shadows, Oosterbaan’s rooms are both conceptually and corporally liberating. Rooted in the traditions of abstract easel painting, they nevertheless abandon the limits of “pictureness” in exchange for a porous dialogue about apprehending experience.

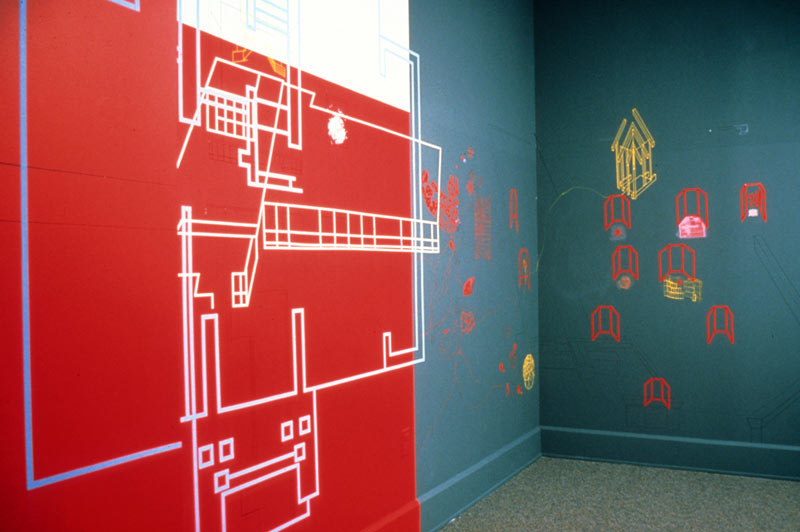

Oosterbaan’s project has an exploratory, searching quality appropriate to phenomenological investigation. Despite her desire to navigate the viewer into, through, and in her environments, she grants the spectator an analog flexibility, a tolerance befitting spaces that privilege every possible position. Her walls are meant to be looked at obliquely, as well as head on. In Room: Site #3, for example, Oosterbaan distorts the plan of a medieval monastery to incorporate the perspectival foreshortening an observer might experience walking toward the wall on which it is rendered (see left-hand view). Implicit here is a critique of the frontality demanded by easel painting and a certain acceptance (or resignation) confirming that a canvas, as she has observed, is “something to walk past.”

Room: Site #3, 2000. Latex, adhesive tape, gouache on wall. Variable dimensions. Installation view. Project Room, Philadelphia.

Oosterbaan’s more recent work has evolved away from cultural references to focus on the conditions of their given locations in the self-reflexive manner of classic, wall-based site-specific installation art. Mel Bochner’s Measurement Rooms (in which the distance between every edge in the room is marked on the wall in feet and inches) and Richard Serra’s large oilstick drawings, are two of the many examples from the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The installations of Jessica Stockholder provide a more contemporary foil. Stockholder and Oosterbaan share a passion for paint’s ability to dematerialize any support, for atmospheric scale, and for what Oosterbaan refers to as “big color.” Their opposing approaches to plenitude, however, are telling. Whereas Stockholder is always throwing in the kitchen sink, Oosterbaan keeps her rooms void of everything but pigment. Despite this openness, and her reluctance to add more objects to the world, Oosterbaan is deliberate about packing as many options as possible into each piece.

June’s Swingin’ All Over, 2003, Oil on panel; latex and adhesive tape on wall and floor; 12 feet x 8 feet x 8 feet; Installation View, Yaddo, Saratoga Springs, NY.

June’s Swingin’ All Over (illustrated on the cover), for example, can be read as a comprehensive index of effects and her dual needs both to concentrate and atomize color. This work includes a movable panel painted to match the wall onto which it is hinged. Demonstrating shifts in value that concern her, the panel helps viewers interpret the work more physically, to see the wall as “built” as much as it is painted. There is also the possibility of reading the bands of color as if they were stacked panels viewed from the side. Generating limitless possibilities of shadow and color, the movable panel is emblematic of Oosterbaan’s attempt to reconcile a frustration she experienced during her initial forays into plein-air landscape painting. Overwhelmed by the temporal changes in light and atmosphere that captured her attention, especially when she returned to the same location to paint on a second or third day, she was challenged by the impossibility of committing to one version of the scene over another. June’s Swingin’ All Over consciously incorporates such variations directly into the body of the work.

The Morris Gallery — the Pennslyvania Academy’s exhibition venue devoted to contemporary art — offers Oosterbaan the opportunity to manipulate space and variable light on a scale unprecendented in her practice. In addition to addressing the room’s angled skylights and scalloped ceiling, her attention has been drawn to the gallery’s new floor, which Oosterbaan regards as a point of departure for this installation. Sensing the glossy, wood surface as “foreign” to the original building’s tiled lobby and handcrafted stonework, she sees the planks as an extensive “plane of color” that can be assimilated with paint (mixed to match) rising up the wall. Parallel bands comprised of reds, blues, and muted colors (on floor panels and applied directly to the walls and ceiling) line the interior perimeter of the gallery. Coinciding with the doorways, ceiling vaults, and skylights, the tinted rings direct the viewer’s gaze away from the panoramic scanning to which we are accustomed and steer our vision upwards. Animated by the momentum of modulated color, they establish the outlines of three massive, penetrable “walls,” as well as paths that invite the viewer to circumnavigate the room vertically. Reorienting our awareness of the thresholds of painting, these and other readings propose unforeseen experiences for this historic space, encouraging us to know it as if for the first time.